After a day trapped inside, ambushed by the deepest, dankest monsoon, Sunday’s dawning brought with it a spectacularly clear sky: and only the northern Pennines, morphing into the majestic Howgill Fells, just waking, to my right – constant, lumbering, reclining colossi – were still snugly covered beneath the cotton-wool-drifted quilt of rising dawn moisture, softening their sharp bulk.

Leaving the motorway, and arriving in the Lake District proper: as I passed Scales on the main road, those majestic mountains reared up in front of me – Blencathra almost friendly, welcoming – glowing a glorious rich russet; with their own topping wisps of remaining cloud floating away, lazily and gently, on the surprisingly lethargic breeze.

All the way, I had followed the sentinel just-past-full moon – a guardian and a guide – the low, bright lunar globe leading me to the turning I wanted at Braithwaite; before descending to its own long orbiting sleep behind the north-western summits.

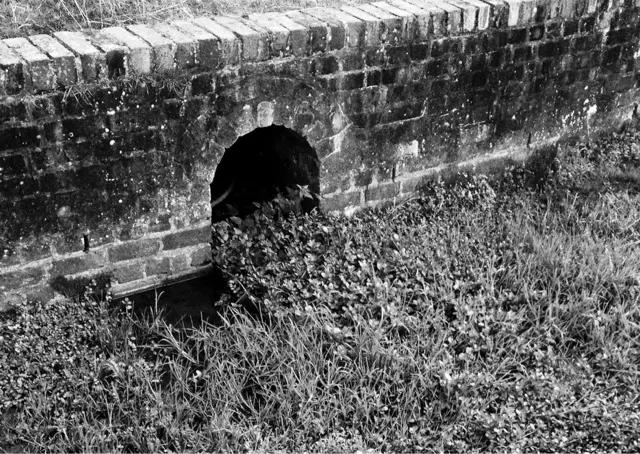

Hugging the Derwent Fells, the familiar narrow road leads to a small, ancient bridge just before Birkrigg – but mouldered now into the grown-riverlike Rigg Beck beneath – the first vestige of the struggles I had, thus far, only seen in the news. Fortunately, the gushing ford that ran next to the footbridge was passable – but only with immense care and forethought. Had I not a vehicle designed to conquer such challenging terrain (and the knowledge to go with it), I would have mourned my annual return to “the lake by the dairy pastures”; but, surely, in this small paradise, readily found another delightful destination. (Cartmel – which my iPad’s autocorrect decided should be “Caramel” – which seems apposite – Priory, again, maybe; or “old man’s mountain” Gummer’s How – surely, on such a glorious day, one of the Lake District’s more achievable, and far-seeing, vantage points? (In August, visibility had been minimal; the ascent and descent treacherous; the weather then damp, belligerent, and bitter.))

Having waded through this first obstacle, still I went on with deep trepidation. At points – especially the final descent, beyond Newlands Hause – torrents of water rendered the 25% inclines deceptive, untrustworthy waterways. Landslips had mostly been cleared; but the surface of the road was littered with debris: mud, wrack, tangled branches, scree. My 4x4 was as sure-footed as a mountain goat, though: enabling me to concentrate with long-held breaths, and steer slowly and cautiously to my morning’s destination.

I was the second to arrive at Buttermere: chatting for a while with the seasoned, hardy soul about to set off to reconquer Haystacks and the ridge along Seat, High Crag, High Stile, Red Pike, before returning via Dodd and Old Burtness.

His love for the mountains was obvious: as was his preparedness. He, too, had arrived via challenges and setbacks – but also would not be thwarted in his goal!

I parked next to Mill Beck, which feeds into Crummock Water. It bubbled and frothed with a rabid anger that had not only destroyed the fences which usually ran alongside, but filled me with a foreboding that I would not be able to complete my planned circuit.

No snow remained: although torrents poured down from every crevice. Water, water everywhere – turning roads and paths into rivers, streams, and sometime waterfalls.

The walk itself was more hazardous than in previous years: well-trodden ways now well under water; sodden ground; routes blocked by serried, toppled, shallow-rooted pines. At one point, I had to scramble along a short rockface: hunting with amazed joy (and the memories of long-forgotten youthful climbing) for hand- and foot-holds – true crag-hopping (albeit in extreme slow-motion) – before descending to the remains of the eroded, slate-pebble-dashed path below. (My damaged body will take weeks to recover from this punishment, I know. But my mind will leap forever with joy at each similar memory.)

Conditions could have been so much worse: recent wrack-marks demonstrated how much higher the mere had lapped – obliterating any chance of traversing its shoreline.

Just past the obstacle course of fallen trees, I encountered a toddler (with justifiably proud mum) entranced with my reflective sunglasses, bush-hat and fingerless gloves. This was one happy child – with an even better outfit than mine! – determined and communicative; and aiming to complete the circuit with a big grin that warmed the heart. I truly hope they succeeded. They deserved to on such a day; and with such spirit.

But, of course, everyone I encountered said hello. Some stopped to chat, as well; and there was a comradely courtesy – holding gates open; advising about obstacles ahead; suggesting diversions… – but all of us glorying in the sunshine hovering above us.

At this time of year – even when all the sun can do is paint the sky a vivid cobalt, and tint the surrounding, cradling peaks with gold flames, without ever reaching the mere itself – this remains such a beautiful, yet sometimes harrowing, place: the true definition of the ‘picturesque’.

I must have been born without the traditional-English-stiff-upper-lip gene: and, as a result, there is a direct line drawn from external, ineffable beauty – whether that be music, art, poetry, sculpture, landscape… – to the core of my creative, sensitive, romantic soul.

Standing once again on Peggy’s Bridge, at the entrance to the Scarth Gap (I expected orcs), gazing back towards my starting point below High House Crag – Haystacks and Fleetwith Pike glowering menacingly dark behind me…… – dear reader, I admit that, silently, I cried.

The overwhelming assault of magnificence flooded my senses. (There was no room, today, for music.) Truly, this is a place where there is a surfeit of glory and grandeur – enough to emotionally sustain one for a lifetime.

I do not believe in any deity – yet this felt like an epiphany, a conversion (albeit on the path to Gatesgarth Farm).

As I returned to the sanctuary of my car, I was rewarded with one of my favourite sights: four keen Border Collies, expertly controlled with the subtlest of commands, manoeuvring a small flock of muddy Herdwicks to less waterlogged pastures.

Such skill; such innate teamwork; corralling them seamlessly and cohesively through a series of gates along narrow tracks. The oldest dog had a withered rear leg – but this was no impediment – this was an independent, sharp spirit, tugging at the boundaries of control, and obviously gleeful in its well-earned freedom.

Later, with such perfect weather for wandering – although, returning to my hotel, I would discover that my cheeks and forehead had been sanded rough and raw by the prevailing wind – the car park behind the Fish Inn grew full; and the paths and roads around the mere grew busy with companion walkers and cyclists. (Last Christmas, I departed as only the second car of the day arrived – such was its peace.) Such busy-ness, this time, made the place safer, though – essential when each turn of a corner presented unexpected vistas and occasional risks.

Not wanting to repeat my morning’s daring adventures, I returned to the A66 via the Honister Pass (which I had been told by my earlier associate was clear and dry) – pausing below the rugged, stunning Seatoller Fell to wonder at the surrounding might. Beautiful Borrowdale (I expected hobbits) glowed golden and welcoming, below, bathed in a beautiful, warm, umber light. But, beyond, yet more stark evidence – an almost infinite sea, where Derwent Water had once lain peacefully: at some points reaching out to stroke the road’s edge. In Keswick, the worst-affected households were marked by cairns of damaged white goods and furniture – and yet the town was very much buzzing with life.

This had been Buttermere at its very best: not as placid and tranquil as perhaps it can be (and is often imagined). But the Lake District as a whole is still struggling: and needs as many visitors, as much help – along with Lancashire, Calderdale, etc. – as it can get. Go visit! Cumbria is open! (But please – with Storm Frank on the way – be careful out there.)