Picture, in the not-too-distant future, Windmill Hill as an island – quite likely, I guess; and probably as part of an Avon-Stour archipelago: with the Edge Hills becoming the local ‘

Mainland’ – and imagine I retreat there, to live out my days, hermit-like, listening – loudly – to Roy Plomley’s

sanctioned eight discs (more likely to be on my battered iPod Classic than a wind-up gramophone – providing Tysoe’s community-funded

wind-turbines are still operating), with my head deeply buried in either Shakespeare or my formidably strugglesome chosen book. What would be on my playlist?

The food of love

1. Kinderszenen

Playing the piano (from a very early age) – most often my mum’s ebony

Model 10 Bechstein upright: gifted to her by

Blackburn Cathedral’s then retiring (but always generous and avuncular) Master of Choristers, Tommy ‘

TLD’ Duerden – and singing (in the cathedral choir), were my two favourite occupations, when I was little: and my first choice, therefore (Kirsty!) has to be Chopin’s

Mazurkas – probably as played by

Maurizio Pollini: one of the most captivating pianists I’ve ever had the thrill of experiencing live.

I inherited my mother’s large collection of sheet music – and a small portion of her incredible musical skill – along with the piano (which now belongs, fully restored, to my son); and my copy of the Mazurkas soon became the most thumbed and Sellotaped, as I discovered how beautifully the music fit my fingers, and varying moods. They seemed written just for me to play.

2. Adolescent angst

Before my voice broke (much, much too soon and suddenly), I was often called on to be the choir’s treble soloist, and loved performing the soaring lines of Allegri’s

Miserere (often managing to sing that top C just a little bit sharp…!). Even now – as the Chopin takes me back to a chilly front room in Blackburn – the Allegri kits me out in a cassock, surplice and uncomfortable Eton Collar, or starched (rough) ruff.

The Sixteen perform this – and the revised (possibly more authentic) version – as beautifully as anyone; and their limited number of voices ensures that each part is heard clearly, with perfect diction and balance. Heaven on earth (which is what all religious music aspires to be).

3. Teenage kicks

Growing up in a house always filled with classical music; having piano lessons every Monday evening with the wonderfully talented, thoughtful and forgiving

Arthur Bury; singing psalms, hymns, anthems, responses, five or six days a week; I suppose discovering ‘popular’ music – mainly through my older sister watching

Top of the Pops on a Thursday evening – was as much a shock to me as the emergence of rock ’n’ roll was to most of civilization in the 1950s. My preference, though, has always been for musicians with skill – and often, of course, piano-based: e.g. Elton John, Carole King, even

Queen (who I was lucky enough to see live, whilst at university). But the idol – of the whole family – was

Neil Sedaka: and I used to belt out

Solitaire on Mum’s Bechstein far, far too often, and far, far too loud! (Due to a quirky family tradition, say “Neil Sedaka” to me, and I will be instantly transported to a motor caravan in a Scottish field: with rain marking insistent percussive rhythms on its roof….)

4. Individualization

During my teenage years, I also began to develop my own taste in classical music: sharing some of them, obviously, with my parents; but also breaking away from their core loves of choral and operatic scores. Initially, it was the

emotion of music that grabbed me: and no-one, perhaps, wears their heart on their sleeve quite as thoroughly as

Sir Edward Elgar (actually – at the time of writing – the seventh most popular composer on

Desert Island Discs; with the seventh most chosen piece of music, in ‘Nimrod’).

The ‘

Enigma’ Variations also happened to be my first real immersion in his rich and skilful orchestrations, his remarkable gift for melody and counterpoint – explored through his own piano transcription (on almost permanent loan from the local library) – but this soon expanded, through the genius of the two symphonies;

The Dream of Gerontius (with

Janet Baker, of course); ’Cello and lesser-known Violin Concerto; to his later – to me, greatest – works: the Violin Sonata, String Quartet, hauntingly beautiful Piano Quintet, and

Falstaff – where his technical skills combine perfectly with his erudition and understanding of (if not empathy with) Shakespeare’s flawed anti-hero. It is a work I can listen to again and again: but no-one interpreted it better, I think, than

Vernon Handley.

5. I must go down

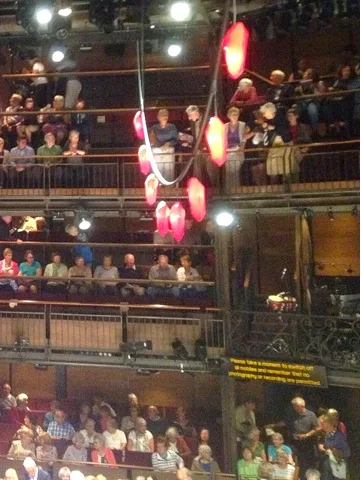

Staying with English music, one of my abiding memories is seeing Benjamin Britten’s

Peter Grimes for the first time: on a grammar school trip. The superb use of orchestration to pull you in to the maritime setting – the humours of the changeable weather; the tempers of the tides – and the wonderful word-setting – captivated me utterly. What greater combination can there be than the best music and the best theatre?

The Turn of the Screw may be more accomplished in some ways – especially in its use of smaller forces – but it is the power of the earlier work that overwhelms.

I cannot hear any Britten without thinking of the late (there is no better word than ‘lamented’)

Philip Langridge – the perfect inheritor of the works written for Peter Pears. No-one understands the rôles as well as he; enunciates or pitches their interpretation as meaningfully. He always found the soul at the centre of the music: and involved you in its interpretation and delivery.

6. So what?

As far as I can recollect, there was no jazz in my life, as I grew up – my parents often bemoaning Radio 3 straying occasionally into such terrible territory! But modern classical composers – especially Messaien and his stupendous

Turangalîla-Symphonie – pointed the way to a medium that, to me, was certainly worth exploring.

I started with the easy stuff – helped on by Alan Plater’s fantastic

The Beiderbecke Trilogy – and found my tastes moving inexorably later, until Miles Davis (with a little help from John Coltrane) almost took over my life. The trumpet’s entry at the

beginning of

Kind of Blue will always make my heart stop; but it is

Birth of the Cool that I find rewards repeated listenings: again, with a combination of technique and emotion.

7. When God created the coffeebreak

I cannot imagine trimming my record collection down, though, without including some (all, please!)

E.S.T..

Esbjörn Svensson was a nice, ordinary bloke who just happened to have a magical way with music; and two good friends who understood, and knew implicitly, how best to make this sorcery come together and alive.

Just writing about them brings a tear to my eye; and makes me realize there is no one track that would suffice to represent the range of their accomplishments. Instead, the record that Esbjörn told me inspired

his musical venturings, will have to suffice:

Jazz på svenska by

Jan Johansson. Esbjörn built on this with the trombonist Nils Landgren – producing two ethereal volumes of

Swedish Folk Modern – but I find them hard to listen to, without wondering what great music the world has missed out on: so it is to the

source of all that inspiration that I will turn.

8. The end

For many years, Beethoven’s

Drei Equali for four trombones seemed the perfect music to accompany my departure from this world. I am not a major fan of this supposed giant of a composer, normally – apart from the piano sonatas, obviously! – although I admit that, occasionally, he produces extended moments of true brilliance (the opening of his fifth symphony, of course…); but these

three short pieces – for a combination of instruments rarely heard together (which, in itself, is sublime: demonstrating that music for brass can be as heartrending as that for strings) – grabbed me by the solar plexus the first time I heard them; and have never let go.

However, here I must cheat a little, and return to the instrument that will always remain ‘mine’, the piano, for my final selection; and a composer that, not only have I met on a few occasions, but that I hope, and believe, will emerge as one of the towering monuments of the last century: Peter Maxwell Davies. Always as lucid in his words as his notes, this is what

Max – a preternaturally modest and insightful man (and a Lancastrian, like myself, who, too, fell in love with the more isolated parts of Scotland – but then made it his home…) – had to say,

recently, on the subject – and on the piece that fits my fingers (and predilections) better than almost any other – even Chopin:

My little piano piece Farewell to Stromness has almost become a folk tune. People just say, ‘I like that piece,’ and they don’t know who wrote it. It gets played an awful lot at funerals these days. And that’s very unusual, for a so-called serious composer, to write a piece that people like so much, and they don’t care who it’s by.

Reading matters

As I presume most people – especially those with a musical bent – rapidly discover, it is nigh impossible to limit your choice to eight records; and, no doubt, on another day, my selection would be quite different. After all, I have over 20,000 tracks on my music server: dishing up jazz, punk, chamber music, heavy metal, modern opera, folk, rap, even works for organ. My tastes are wide, eclectic, sometimes bizarre, span seven centuries, and most of the globe.

The same can be said – just about – of my taste in literature; and my thousands of volumes of poetry, biography, science fiction, modern European literature…. As I have never got on with the immensely popular operas of Verdi, Puccini, etc. (although I love

earlier operatic works, up to Mozart; and more

modern ones, such as by Britten, Tippett, etc.), I have never gotten into those books that many seem to imply are essential classics: e.g. Jane Austen, the Brontës, Dickens (although I

adore Wilkie Collins).

My love of Shakespeare is obviously satisfied by its standard pairing with the Bible (although I would rather explore the Hindu epic

Mahabharata or the many

sutras of Buddhism). But the book I have finally chosen – and I know this is immensely specific – is the green pocket 1923

The World’s Classics edition of

Moby-Dick or The Whale that I picked up, on the spur of the moment, in 1997, in a second-hand bookshop on my first ever visit to Hay-on-Wye, for the princely sum of £1.50! (It even comes with an integral red, silk, woven bookmark.)

I have read this many times – and with each reading comes fresh discoveries, greater understanding, and a yet deeper admiration for the skill of the storytelling; the use of words to conquer up complex images; and the vein of sheer awfulness and brutality that Melville works into nearly every page. There is a big heart at the centre of the book: and, as with music, it is this that always pulls me in – along with its technical accomplishments. I just cannot get enough of it; and know of no better tutor in syntactic craftsmanship. The print is small, though: so I will have to blag a magnifying glass outside of my chosen luxury.

Life’s little one

I haven’t played, or owned, a piano for quite some time – not since my hearing began to

fade. However, this will not stop me from banging away, like the dying Beethoven, at the keys of, hopefully, a Bechstein

concert grand – if it can be made to fit inside the windmill!

Re-learning the instrument (providing it comes equipped with a couple of centuries’ worth of music; and a comfortable, adjustable stool) would keep me occupied for most of each day, I think; and, being surrounded by water, there would be no-one to drive away, apart from the gulls! Maybe I would attract a chorus of dolphins or seals…?

But riddle-like lives sweetly

As to narrowing down my eight discs, I may as well stick a pin blindfold in my entire music collection. I think, though – which will leave my parents despairing! – it has to be the Miles Davis. Brass band music with a lilt.