Although now fashionable – and popular – Henry IV, part I (on at the RSC, in Stratford-upon-Avon, until 6 September 2014) has always seemed to me a problematical play: which depends too critically on an evolving, heroic Hal; and finely-tuned balance – between the bawdy and the political; the contrasting fatherliness of Falstaff and Henry senior; the hysterical and the historical. When first presented, it also had its critics; and Shakespeare’s struggle in writing a play ostensibly about a monarch hated by Queen Elizabeth I, I think, shows through – however much of his customary effort and skill he uses to disguise the fact: instead drawing much stronger characterizations of those around – and opposing – the king: pushing him so far into the background that it can be hard to understand his motives and motivation.

It is all too easy, therefore, to get swept along by Falstaff’s robust posturings and canny wordplay: and an excellent portrayal – as is, undoubtedly, Antony Sher’s (albeit with strong echoes of the great Anthony Quayle) – can readily wipe out some (maybe most) deficiencies in other areas. However, I still left the theatre, last night, slightly disengaged. Perhaps, part II, in a couple of nights’ time, will remedy things? (Having Henry V continue the series – after such a gripping Richard II, last year – would also help. But it is not to be….)

For me, Trevor White’s mercurial, almost Hamlet-like, Hotspur was a revelation, though: switching naturally from ecstatic hops, skips and jumps around the stage to tart depression, insolence, arrogance, anger and neediness. He engaged me much more as a romantic hero than Alex Hassell’s Prince Henry; and therefore made me so want him to survive (if not win) his fatal duel (superbly choreographed by Terry King) with his royal namesake – who seemed much more at home in Eastcheap than a suit of armour.

In contrast, Hal’s development – especially the (sudden) contrition shown to his father – seems forced. But then, perhaps that’s the point? However, knowing how the plot develops, I believe it should be more of an obvious turning point – from boy, spoilt, and with no responsibilities: to a prince bearing the weight of England (and a future crown) on his head – than a simple act of appeasing Daddy….

The renditions of Owen Glendower (Joshua Richards: who, as Bardolph, gave Sir John almost as good as he got) and the Earl of Douglas (Sean Chapman: who excelled as the Earl of Northumberland in Richard II – which he briefly reprised here) also seemed slightly cartoonish – and I don’t know if Douglas’ stripe of facial blue paint was a tribute to Braveheart or Alex Salmond. As with David Tennant’s fey hairpiece (as Richard), we certainly got our money’s worth from the wig department, though!

Paul Englishby’s stirring music played more of a starring rôle, here, than in Richard II – although I preferred the sparseness of voice and brass in the earlier play: punctuating and announcing scenes with perfectly-nuanced, repeated themes. Here, it acted as more of a soundtrack: trying to pull together deficits in momentum – although any binding leitmotifs seemed lacking.

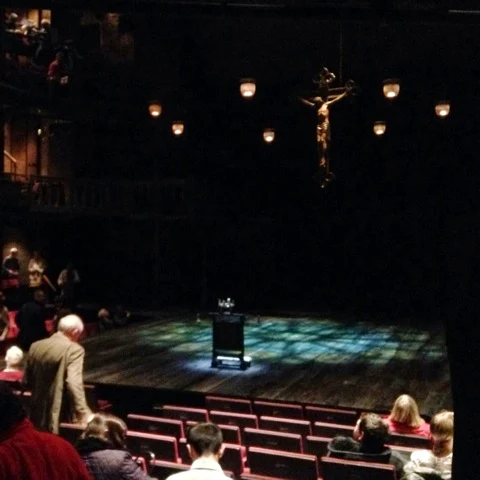

The clever set design, by Stephen Brimson Lewis, also echoed that of his work on Richard – as did the lighting of Tim Mitchell – although, again, neither made quite the same impact.

Overall, well-worth seeing: especially if you’re going for the comedy rather than the history. But, for me, it wasn’t quite the delightful surprise that Gregory Doran made of the first of the Henriad tetralogy.

No comments:

Post a Comment