It is not the entwining ivy, the golden jasmine, the clinging honeysuckle, and the trained rosebushes, with their delicate perfume, to which I desire to introduce the readers of the Advertiser, but the real life lived by the labouring poor in the villages of Warwickshire.

– Joseph Ashby: Warwick Advertiser (24 December 1892)

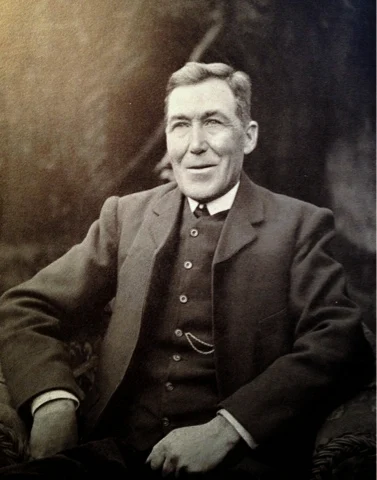

Just opening it – and breathing in that musty-but-sweet perfume so redolent of old pages, old literature, old lives – instantly connects me more firmly to the land I live on, the village I live in (as well as whisking me back to the libraries of my childhood; the encumbered shelves of my parents and grandparents). Reading it – and admiring the wonderful, insightful, unique narrative and style – I am immersed in the history of our village: seen through the eyes and experience of a

man whose knowledge, wisdom, understanding, ambition and graft – and importance – I can sadly only appreciate from afar: as he was born just over a hundred years before me (and his biography).

He would, though, I am sure, have made a good, lively and true companion, wandering and riding around the highways and byways of his village… – although what he would make of its current manifestation, and the threats it faces from developers, I can only imagine. I believe he would have fought such menaces, though: as he always did so keenly for the causes he so strongly believed in – with “an economy of indignation… saved up for the big things and kept turned in the right directions.”

Time showed in fact that Tysoe men could not be won for vast schemes; they wanted this wrong righted, that foul spot cleared, and reasonable scope for a man’s activity. They had, the best of them, wise inherited attitudes outlasting the occasions of learning…. But though they were sceptics, they saw that there were good men in all ranks and grades, and moreover, that in all but the worst time, everybody, just and unjust alike, contributed something: the foolish amused and the wicked instructed. They saw men as members one of another.

Early in her book, Kathleen Ashby describes the situation of Tysoe in the mid-nineteenth century: the small world her father emerged into (fatherless) – not that so much of our topography has changed… – setting it against its neighbours:

Compared with all these Tysoe had some high distinctions. It was large, and composed in a rare way. Its trinity of hamlets, Upper, Church, and Temple (or, as the old maps had it, Templars’) Tysoe were large groups of houses strung along the foot of the Edge Hills. These, with their minor clusters and lanes, stood on small brooks flowing down parallel courses some quarter or half mile apart. The hills themselves were unique and, moreover, sacred. They looked high and straight, fully their six or seven hundred feet. From their ridge, they are seen to be the edge of a plateau, not straight but a series of curves, forming great amphitheatres, suitable for giant Roman dramas and spectacles, but no one in Tysoe thought of those. For [many of the villagers] they were biblical hills – steadfast, a glimpse vouchsafed of the foundations God has laid, the bastions he has built; yet sometimes skipping like lambs, while clouds that are the skirts and fringes of God’s raiment sweep along them.

Such beautiful, expressive, poetic prose (anything but prosaic): which she also implements in fluently and naturally capturing the villagers’ argot – and without any fuss, pretentiousness, or exaggeration. It rings real and planted; consistent and true… – although she knowingly contrasts this “local mode” with her grandmother’s use of “book language”, when required! She also builds foundations for her writing on those of her parents’ possessions important enough to her sentiment and identity, but essential to the verisimilitude of their lives – such as Joseph’s first personal books: bought in Banbury with three shillings wisely and affectionally gifted by his mother, Elizabeth, from the family’s scant harvest gleanings – delving for documentary evidence; handling them affectionately and with reverence: much as I now do with her creation (and which, with her scrawled dedication, produces similar significance and interconnection).

How did those people live and work? Why did they stay – or move away? What attracted them? What made it hard for them? What made it hard for them to stay or move away?

…and Kathleen’s

A Study of English Village Life goes a very long way to answering that: stretching back centuries in a precursor to – and analogue of – Ronald Blythe’s wonderful, immersive

Akenfield: another book that I believe is fundamental to understanding the evolution of rural life; and its frequent foundation in poverty, as well as in tilth.

When her father was alive, the

Act of Parliament that was passed in April 1796 “for the enclosure of the open fields of Tysoe” – almost the last parish in the area to succumb: and, therefore, with little apparent resistance – was a recent and living memory; the end of an era (with even the “Red Horse itself… penned up within hedges, without even a footpath past it”). Many of the pre-enclosure rituals were still enacted at harvest, though; and many villagers were still aware of the location of their family’s ‘lands’, or ploughing ridges – a passive, subtle, but behindhand rebellion against “a visible sign and symbol that rampant family and individual power had gained a complete victory over the civic community.”

“Enclosures would have done good if there had been justice in ’em. They give folks allotments now instid o’ ther rights – on a slope so steep a two-legged animal can’t stand, let alone dig!”

But Joseph, as he ripened each summer, with the crops, was also interested in the wider world:

Three things came to him in this period; some idea of how events elsewhere affected his own home and village; some knowledge that other communities produced other manners and other men; and then the sense, to describe it as best I can, that under the wide acreage of grass and corn and woods which he saw daily there was a ghostly, ancient tessellated pavement made of the events and thoughts and associations of other times. The historical sense he shared with many of the men he met about his work. Their strong memory for the past was unimpaired by much reading or novelty of experience, and yet their interest had been sharpened by the sense of rapid change.

In many ways, Joseph – with his political understanding, cultural immersion and regular contributions to the (then very) local press – was the original Bard of Tysoe: more social and forthcoming than I, though; and with a more monumental and commanding presence – an organizer of men and causes, as well as of words and ideas.

Although “talk was his medium… he was a lifelong writer of one kind of thing and another.” Sadly, though, “there remain only printed fragments or faded manuscript sentences” – a fact that makes me hesitate, and then meditate on the future of my words, in a period when we no longer relish and rely on the almost-permanency of “old pages” and “encumbered shelves”; but commit our thoughts to flimsy, fleeting pixels, viewed transitorily, rather than stacked and cherished, to one day be visited again with delight at the conclusion of a successful forage for a familiar, half-remembered phrase or sentence.

“He liked to write as an onlooker, wide-minded and kindly, indulging, I think, in the fantasy of being at ease as to time and income…” – a sentiment, and an ambition, I empathize with (but have not yet attained). He also, like me, “must have found time to read books on history and rural affairs, or his writings could not have achieved their quality.” He wears his learning lightly, though; and always parallels it with action: using the conclusions he arrives at, with great thought, to understand, strengthen and animate the lives of his peers; to “arrive at the facts [that] would make ill-informed talk an anachronism.”

This devotion to knowledge, passed down from his mother, flowed naturally to his offspring, as well. He believed that “it was always important to notice how things appeared to children” – and his, inheriting his love of Tysoe, as well as his talents, “firmly believed themselves to live in an area of remarkable natural beauty. To them the Edge Hills were high, though not too high for one to stand often on their top and look out over the world.”

Kathleen – as his natural, bardic successor – reproduces, towards the end of the book, her first (although not childish) attempt at capturing the Tysoe she saw, felt, lived in, and loved:

We no longer see our country as did the old painters, the distance dark and threatening, the great elms near at hand admired for strength, their leaves individually drawn as each a sign of life and power…. Looking from the top of Sunrising our landscape is friendly to its bounds; we interpret its light and shade with the great Constable’s help to mean corn and plough and meadow.

From below our hills are high: “Man lifts up his eyes to the hills.” In the vale is a man’s home; the market and the milkpail. The poetry of these may be more profound than that of the heights but it is not easy to feel it so. On the hills is exhilarating wind. There in June the harebells and thyme “waft prayers and adoration to the azure”, the firs on Old Lodge toss their boughs in a rarer, quicker, air. Here a few romantic young folk load the wind with shouted poetry. Many through the nineteenth century have thrilled to feel their minds expand with the wide view. “Yonder see the Coventry spire”, they say, or “as far as the Severn”, but what they mean is that here the soul is large and free. These long-sighted folk are mostly men taking a Sabbath walk. On Sundays village women are busy dressing each member of the family, in Sunday best, and then afterwards cooking the finest, largest meal of the week, but here they come on summer weekdays gathering mushrooms or blackberries. It is difficult for them to shed the numerous and pressing cares of the household, but gradually in the keen air sight and smell become heightened, hands fall idle and the gatherers note the tiny flowers and the cloudlets in the sky. It is animal life that attracts the little children; they like to frighten the clumsy sheep – so often it is they themselves who have been afraid. They fly with the birds that are freer even than their holiday selves. The bigger children remember that they came here in February, when the wind was at its keenest, to chop boughs and pick up chips from the trees that had been felled. The pale sunlight and the pale primroses asserting themselves against the cold had promised summer and now the promise was fulfilled. Very soon the visitors to the hills return to their life of custom and work in their homes below, but they will come again when time and labour permit, to look outwards and heavenwards.

However, her “study”, written half a century later, concludes with these words – bringing us back to her father… – words which I cannot better:

It has been the special destiny of Englishmen to be at once good citizens and highly individualised – to be very serious pilgrims, like Bunyan’s, but telling fine tales on the way, like Chaucer’s. The scale of our lives is different now; for us all the world is our parish; all the more need to practise our wits and skills in Joseph Ashby’s way, on the home acres.