…I’ve been for a walk on a winter’s day: well, autumn’s – but that breeze, “after summer evermore succeeds”, truly felt like “Barren winter, with his wrathful nipping cold” puckering at my face and fingertips. Certainly: “Life’s autumn past, I stand on winter’s verge”. And with meteorologists marking the season’s change on the first of December; last weekend’s bitter frosts; and only just over eight hours between dawn and dusk; it really does feel like “dead-cold winter must inhabit here still”.

When clouds are seen, wise men put on their cloaks;

When great leaves fall, then winter is at hand;

When the sun sets, who doth not look for night?

Untimely storms makes men expect a dearth.

All may be well; but if God sort it so,

’Tis more than we deserve or I expect.

– Shakespeare: Richard III

Our young oak discarded almost all of its leaves abruptly and unceremoniously in the recent gales: scattering them far and wide – and only a small handful of hardy, corroded bracts still flicker tenaciously but tenuously in its stark silhouette. However, wandering around the area between Baddesley Clinton and Packwood House, on Wednesday, I noticed that most of the oak trees there – albeit more full-grown; and huddled together, in damp, deep, fecund ground (some of which still clings to my poor boots) – yet hoard their marcescent foliate treasures: with glowing, backlit hints of jade amongst the gold and bronze; vivid under the gelid sun, against the sapphire sky. (Who needs a rainbow…?)

These more-developed specimens stand in the precise line of a hedgerow (above) that had not long been flailed, military‑style, within an inch of its life – if not just beyond. Cropped so short that I could easily see over it; and transparent as chicken wire – despite a large uncultivated strip between crop and boundary – this act of agricultural barbarity has left no shelter for any overwintering flocks; and therefore no chance of sustenance from within its boughs. The deep marshy tyre-tracks also showed how very recently this savaging had taken place – the footpath churned into a series of treacherous ankle-snapping, puddled diagonal ridges.

If this compulsive cut had been set against a major thoroughfare, I would have had a little sympathy, perhaps. But this was well-removed from civilization, between two extensive arable fields; and seemed to represent an over-attentive brutal addiction to unnecessary neatness for which I can conjure up no justification. As Nicola Chester – one of my favourite observers of the natural world – recently opined: “It’s the hedges way off the roadside that get me; tractor tracks slewing all over the verges and for why?” And she described my recent encounter with a decapitated waymarker as “Ridiculous, extreme unnecessary hedge cutting!”

I would hope, as the warmth returns – bringing with it our summer flocks – that these torn branches – already “too short and thin”; and just as they begin to recover, with their emanating buds – are not subjected to the same repeat indignity: leaving no space for nests, huddles of sparrows, retreating small mammals or endangered moths and butterflies. (Although, with a rule change effectively banning such trimming after the first of March, each year – unless in exceptional circumstances – I am starting to feel a tad more confident….) Such an action, then, would reduce the availability of food for any emerging chicks: and it is no wonder, therefore, that the RSPB is concerned about the future of agricultural wildlife – especially when you learn that “over 40 years the long term decline in farmland birds is 50 per cent”.

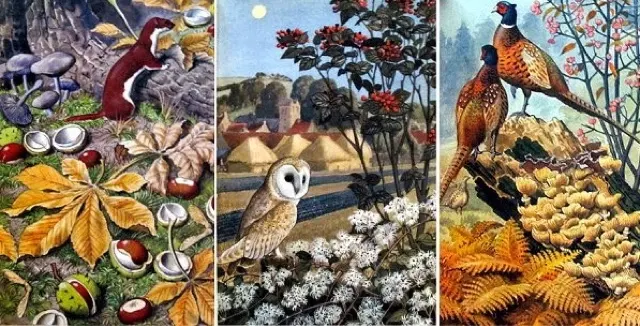

I do understand why hedges are trimmed. [Although, in my day – nearly forty years ago – this was a more intensive, manual undertaking: and the small mixed farm I worked on was run by a family who cherished the brambles and the resultant, eager wildlife. (If you truly want to see how much has changed in a few generations, the Ladybird book, above – What to look for in autumn – from 1960, reads like ancient history.)] What I don’t grasp is the seemingly modern trend of too-frequent, over-enthusiastic, reiterative cutting: especially where – as here – such wide field margins exist: which surely negate most of the reasons for this intrusive (and expensive) form of land management in the first place.

If farmers want to reinforce their credentials as custodians of our natural environment (not that there are many – if any – places truly wild, or “natural”, anymore, on this small island); and keep the respect of those who also use and enjoy the land, then perhaps they – although accepting that many already do… – need to apply a little more thought (along with the Government, of course), and balance the social issues with the economic. Just imagine the outcry if our mature oak trees were all trimmed so severely every year.

No comments:

Post a Comment