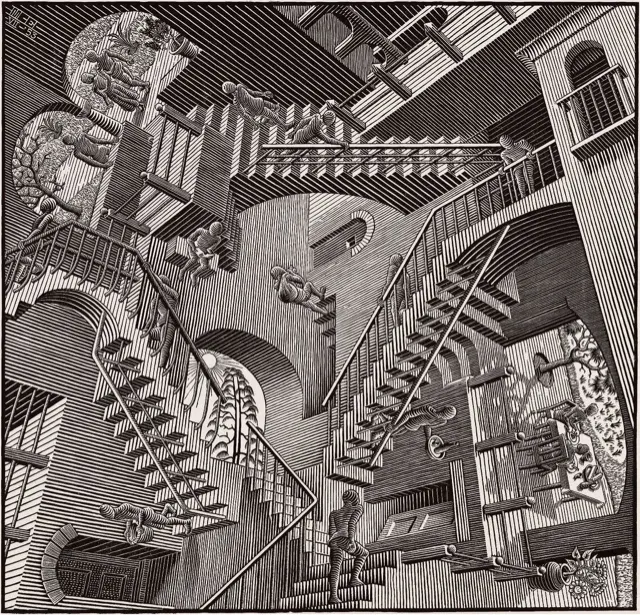

Yesterday, sat in the wonderful, Escher-like foyer of the Royal & Derngate, I wrote that I was…

Returning… to see the all-important captioned performance of King Lear (“lured”, this time, by every single member of the company…) – knowing, as always, that there would be elements which had evolved since the preview we saw; as well as moments of magic that I had not entirely absorbed….

As flies to wanton boys are we to th’ gods,

They kill us for their sport.

This allusion to Escher’s Relativity seems even more pertinent when you consider both the “experimental” language and structure – the texture – of Shakespeare’s lines. Not only, characteristically, do we seem to be stepping between different worlds (ones driven, held together – however flimsily – by madness and sanity; religion and atheism; faith and deception; love and hate; fortune and misfortune; anger – of people of gods, of weather… – and peace (all dark and light, if you will)); but, in this production, in particular, the number of characters addressing us, the audience, directly (even if only for a moment, as in Goneril’s “No”, in Act 5, Scene 1), immerses us in different, contradictory, orthogonally-opposed, world-views (more formally, that wonderful word ‘Weltanschauungen’).

There is one scene (Act 3, Scene 6) – “A chamber in a farmhouse adjoining the castle” – which will stay with me for a very, very long time (as will the whole night): where Kent, Gloucester, Edgar and the Fool… – all seem to be talking at cross-purposes. Everyone is, essentially, mad; pretending to be mad; professing madness; scared of going mad; or attempting to see through Lear’s own madness (if it is such…). This was given full, chaotic, rein – and reminded me how ‘experimental’, when compared to the majority of his plays, Shakespeare really can be. Not only do we get characters driving on the story with expositional soliloquys; but there was an almost Beckett-like intensity, here. Is this the template for Endgame – 350 years ahead of its time…?

Seeing it again brought home to me that attempting to multitask (i.e. watching words and action separately/alternately) in this way actually removes you from the action quite a bit: not acting as a barrier, per se; but leading to a lesser immersion (and increased distraction…).

I wonder whether the captions for King Lear will hamper or assist…?

Although (as above) I have repeatedly questioned the value of captions for those, like me, without much ability to hear, this time they proved their worth, their usefulness: opening up those different spheres – both exploding them, enabling greater forensic examination; and shedding a crystalline light.

Friends, Romans, countrymen, lend me your ears. I come to praise Captions, not to bury them.

This may have been down to the Visual Sound Live system used (new to me), and its placement (effectively, two large HD television screens, either side of the stage, level with the actors’ eyes). However, I am also starting to wonder if there is a ‘quality threshold’ in performance: that is, when a production is utterly wonderful – as this one undoubtedly is – the captions become almost subliminal, and add mightily to the experience. If it is not already so involving, then they simply act as that “increased distraction”.

As well as I know the play, I do think you need this clarity of language to fully appreciate its rich “texture” – and this was helped, here, by the company’s consistently distinct delivery (and in many natural accents – which, for me, added even more exquisiteness and strength: this was a court composed of subjects from the four corners of Lear’s Britain). There were thus quite a few occasions when I realized I had not looked at the captions for quite some time!

I therefore did espy many “elements which had evolved since the preview we saw; as well as moments of magic” – the most touching of which revolved around Lear’s love of those who love him. His repeated tight, tender grasp of the Fool – surely one of Shakespeare’s most beautifully-etched relationships – for comfort (of both of them); his gentle kissing of the top of the blinded Gloucester’s bald pate; and, of course, his (and Kent’s) reunion with Cordelia.

When thou dost ask me blessing, I’ll kneel down

And ask of thee forgiveness.

Joshua Elliott (Fool); Michael Pennington (King Lear); Tom McGovern (Kent) – photo Marc Brenner/Royal & Derngate

There was also more laughter than I remember the first time around – as if both the audience and company had somehow jointly gained in confidence in their exploration of this great work… – bringing yet more contrast; more profundity. Pennington’s energy, as he cavorted from “this great stage of fools”, eluding his captors, was a thing of joy and amazement – and brought the house down!

Then there’s life in’t. Come, and you get it, you shall get it by running. Sa, sa, sa, sa.

Having listed every member of the cast – “all of whom were equally astounding” – last time, I will not reiterate their strengths here. (I will make amends, however, for not mentioning Alison de Burgh – director of some truly vicious fights – and Karen Habens, “Deputy Stage Manager on the Book” – i.e. the crucial kingpin on which the whole evening revolves; and perfectly so.)

I should also stress how much – even after such an incomparable preview – ‘tighter’ the production feels; how little details (which I may have missed, then) add depth; how the whole performance has, somehow, grown. This is the King Lear to beat (not that I think it can be…) – and I am almost (almost) tempted to return my ticket for the RSC’s production, beginning in August (were it not for Paapa Essiedu as Edmund, and – God be praised… – David Troughton as Gloucester (yay)).

Adrian Irvine (Albany); Sally Scott (Regan); Scott Karim (Edmund) – photo Marc Brenner/Royal & Derngate

So there’s not really much more to be said. This is Shakespeare as (I believe) he should be: uncannily relevant and insightful; with coherently-defined and clear-speaking three-dimensional characters (whose motivations you – eventually – comprehend); and lucid plot-lines that bob and intermingle, diverge and re-emerge, but finally entwine – ensuring that three hours of drama “Holds in perfection but a little moment”.

No comments:

Post a Comment