I hope, dear reader, that you may be one of my descendants, but I have only three children, my grandfather had six and as I write a German aeroplane has circled round above my head taking photographs of the damage that yesterday’s raiders have done, reminding me that there is no certainty of our survival.

If you are not one of my descendants then all I ask of you is that you love the country as I do, and when you come into a room, discreetly observe its pictures and its furnishings, and sympathise with painters and craftsmen.

– Tirzah Garwood: Long Live Great Bardfield: The Autobiography of Tirzah Garwood

After three extended, extremely leisurely and exhaustive visits to Ravilious & Co: The Pattern of Friendship (English Artist Designers 1922-1942) – Compton Verney’s latest wondrous, desire-indulging display (of everything from the smallest hand-carved print-stone to a documentary on a now bomb-ruinated mural) – I had already discerned that much more time would need to be spent there (at least to produce this ‘not a review’); but that, even then, my absorption and adoration would, could… never be quenched. In fact – apart from experiencing, in the flesh, Janet Baker singing in Elgar’s The Dream of Gerontius (which I am fortunate to have so done) – I had quickly grasped that, as a resolute atheist, this is quite probably the closest to any divine being (albeit as evoked by the most tempting graven images) that I shall ever come. The thought of its absence – as with Moore Rodin, at the same venue – although amplifying my attentiveness – rapidly causes my vision to blur.

This, then, is more a personal response than a review. Especially as – never having seen Ravilious’ watercolours in the flesh before – I was initially too overwhelmed to delineate my reactions. What I will say is that we are immensely fortunate that such a wonderful facility as Compton Verney exists (and on Tysoe’s doorstep, too) in which to exhibit them: and I would, therefore, encourage everyone based locally to go (at least twice: there are so very many riches on show) as soon as they are able. You may not see them in the same way, the same light, as I (which is, of course, A Good Thing); but I guarantee that you will find at least beauty… – as well, I hope, as a personal connection that lingers for a very long time afterwards.

Crossing the Adam or Upper Bridge that leads to the gallery’s entrance, the first sighting of John Frankland’s Untitled Boulder of Portland stone always pulls me rapidly back to its Dorset (and Jurassic) origins – having lived on that magnetic county’s border for a short while, over a dozen years ago – whilst simultaneously lending concrete form to the anguished angular imaginings of Paul Nash; as well as his own deep connection to the liths and other lost-in-time creations so frequently found in that region’s mystical masonic landscape.

There is an almost hollow, harrowing lack of humanity in many of Nash’s creations (his brother John, whilst, on the surface, similar, producing much more gentle interpretations); and so it can be with Ravilious: who was, along with this exhibition’s esteemed company, a pupil of Paul’s at the Royal College of Art (RCA). It is not that the personal is lacking, per se: but that you have to engage with the works to comprehend it. That is, “the personal” is often insinuated (by objects; by absence; by a recognizable recent presence): but we see it through the artist’s eyes; we feel his response; but its lack then tugs at our own reaction.

I empathize: probably due to my Asperger’s, my drawings also lack such “humanity” (I never had the patience or convinced confidence of the wood- or steel-carver: any reproductions were therefore dependent on the printer’s deep learning and practised skill) – not so much a misanthropic missingness; more a belief that the land I saw, although always sculpted to meet man’s needs, was utterly self-reliant; was ancient; and would thrive still (or probably more) once we had erased our selfish selves from its habitation.

…the porter looked at the painting and said that the landscape was alright but he didn’t think much of the figures. It was true that Eric wasn’t very interested in people as subjects to draw and found it difficult to adapt them suitably into the shapes he wanted them.

[Eric] liked the drawings and engravings of people that I made, though I hadn’t very much interest in landscape which he loved. He liked my work because it was personal and didn’t imitate his own.

We have, I believe, his long-suffering wife, Tirzah – one of the most important influences on Ravilious – to thank for the increasing frequency of more animate, more vibrant, more involved human beings (when required). [She – as great and wide-wandering an artist as her husband – injects some of the humanity (back) into Ravilious’ productions more by simply being, than affecting his style(s), though.] And we must also thank Andy Friend (co-curator of this exhibition; and its patient, thorough researcher and recorder) for explaining the how and why. (His beautifully-realized book, Ravilious & Co.: The Pattern of Friendship, is exemplary in its clarity; its weaving and unwinding of parallel lives; its presentation of the finest detail – as with its subjects – amassing a weight of insight and feeling).

Ravilious – usually a most social fellow in the flesh – sees deeper than the majority of mortals (and beckons us to follow): his “imagined realities” a rare combination of self-found technique, evoked beauty, and a troubling sense of fragility. (This is the same brittleness which dreams possess, as they atomize just beyond the borders of memory, despite their momentary immensity of reality and complexity.) Sometimes, therefore, the initial glance (or even longer stare) feels as if it is through gauze, or the dawn’s dazzling new net curtains: an impression bestowed upon us by the pale deftness of technique, combined with a palette birthed and dispersed by the sun’s haze- or cloud-filtered beams.

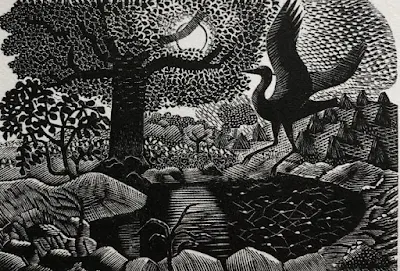

However, although there is such an Impressionistic dreaminess (and sometimes plain, but justifiable weirdness) to many of the large works (Ravilious as “the Seurat of Sussex”) – especially, I suppose, because of his not-quite-habitual, but somewhat manneristic, application of repeated short brushstrokes (some of them appearing to have been fashioned with a miraculous dryness…); and of leaving the paper to generate its own incandescence – the more you gaze into them, the more (either pencilled, or dark- and fine-painted; seen with the lithographer’s eye) detail there is to be found. And it is this precision [the very same quality that makes Ravilious’ woodblocks so utterly astounding (see A Rust-Coloured Feruginous Light (below), for example)] – almost hidden within a vapour, or veil of imagination – superimposed upon a rich base of reality – that, I think, makes the works utterly special.

Ravilious I have known of for as long as I can remember: an interest in the sad, suffocating arts of war – poetry, print, music: all delving deep for comprehension that often will not come… – having led me, via the astonishing Paul Nash; Shostakovich sounding in the background; Wilfred Owen grappling with my heart in the foreground – to his dumbfoundingly massive continuum of talents. But I had not known of Garwood; had not been conscious of many of those featured here (Edward Bawden, Helen Binyon, Barnett Freedman, Thomas Hennell, particular favourites) – despite my belief that British creativity peaked in the first half of the twentieth century (or maybe shortly thereafter…).

The watercolours have a vivacity that cannot be reproduced in print – Norway 1940 (above), an early war painting, glowing with insubstantial serenity, my best-loved [a game we all surely play surrounded by such great art: choosing the one we would steal; or at least love to own; to cherish and stop us in our tracks every single day (as simple as selecting our favourite father…)] – but the woodcuts do: because that was, of course. their purpose! The skill of observing minute detail, of reproducing it, along with whatever emotional and physical processes that entails – so fundamental to the paintings – is thus made concrete. (And how.)

There are direct personal links to Hepworth and Moore, to Enid Marx; but less tangible threads are sewn into the tapestry of British art which would follow. At one point, we hear the music of Benjamin Britten (wryly commenting on the documentary The King's Stamp – Ravilious’ great, equally-talented friend Freedman looking lost and wooden); and Tippett appears briefly in an outer circle of artistic dramatis personae. And who can now see David Hockney’s early analogue works, or his later digital and seasonal ones – Woldgate Woods and Bigger Trees Near Warter, for example – without steering the use of a peculiarly English vision back to those already detailed?

The exceptionally wide range of art on display includes a beautiful, soul-hugging portrait of Freedman by William Rothenstein, Principal of the RCA. This captures the subject’s humanity with such great understanding and empathy: generating just one of many extended moments where the world fades away, your heart stops, a tear coalesces, and you are alone, now, in the communicative presence of what can only be deemed as ‘genius’…. (It is Rothenstein – whose presence runs quietly through the exhibition like a brook we sense but cannot always see… – who must claim the ultimate credit of corralling all these talents; and believing deeply in their creative worth; their explorations beyond existing artistic borders….)

After long visits, not only Compton Verney’s parkland, but the local landscape has become populated with Paul Nash trees; John Nash hedges; Binyon streams; and the immersive rolling downs of Ravilious. (Any passing characters, or those which inhabit these peaceful scenes, belong, of course, to Bawden, Binyon and Garwood.) However, although I now see with my hero’s eyes, I will never be able to draw with his hands….

By the way, do not – extrapolating from a life cruelly snuffed out – believe or suppose that this unique style was frozen; that this is what ‘mature’ Ravilious would always be like. Gaze into the hardness of Norway 1940, or the dark flames of contemporary HMS Ark Royal in Action No. 1 (right), and you feel – if not see – the transformation (part of the constant evolution) of all great artists.

The sadness in these paintings stems not (merely) from their subject – “My subject is War, and the pity of War. The Poetry is in the pity…” – but the change, the maturity, as it accelerates and compresses in the creative processes of those so immersed; combined with the fact that the artist’s sacrifice means we can never see its outcome. [I struggle, I must admit, to calculate which is the greater loss (to humanity): the one person, or the multiplicity of works that we will never inherit. Of course, you may say: had Ravilious – or Owen – survived, so would their then-future productivity. But who knows what other transformations, begotten by savage conflict, would have been worked upon these so-resurrected soldiers by their survival into the ensuing uneasy peace. That it would be different to a productive life lived without (or outwith) war is neither a good nor bad thing, and cannot be measured. All I see, all I know, is that, out of conflict – external and internal – has emerged so much great art. But, no, I do not think the loss of its producers can ever be compensated for: not even with such greatness. There is just a niggling itch (buried so deep in my brain that it may never be scratched) that, as my grandfather very rarely, very reluctantly, discussed the fighting he took part in, so any artistic returnee may return from “the front”, their creativity similarly cruelly muted; their artistic tongue ripped savagely from their mouths. This seems, to me – in the erasing of what must have felt a pure, driven, singular raison d’etre – I ink, therefore I am… – a punishment truly worse than death.]

On the surface, gazing at (rather than into) a succession of Ravilious’ watercolours could easily begin to feel ‘English’, ‘pastoral’, and ‘nostalgic’ – falling prey to the (possibly) unthinking artificial sweetness that many seem to attribute to Vaughan Williams (especially his omnipresent – but no less beautiful – Lark…). Those who do so are unlikely to have sat, shocked backwards into their seats, by his symphonies (especially the violence of the Sixth); nor do I think that they consume their art beyond its face value: they see prettiness where I see a struggle for understanding, and for new definitions of the aesthetic (including ruined farm machinery; paddle-steamers; weapons of war…) – definitions that, to me, have a leftwards-leaning political bent: but could be seen, perhaps, as more humanist than socialist.

Made obvious in the war paintings – the immersive Dangerous Work at Low Tide, 1940 (above), for example; as well as the studied portraits of submariners – I see Ravilious fighting to encompass his place, humanity’s place, in the world (or at least – from the viewer’s perspective – microcosms of it). Why is this here? How does it work? A frighteningly-accomplished engraver, he must have been enthralled by the mechanical: its design and purpose; its usefulness; its relationship with those who used it, and required its use.

This – as Alan Powers has argued before me (and more cogently) – is therefore political art (but only politics as faith, rather than as in organized, high-church religion); and should (as it does for me, anyway) be seen as such. It is the sage, earthy words of John Clare given extra, harrowing flesh.

The morning before he was due to leave, he got up early to make the breakfast and standing in front of the mirror putting on his tie, he said: ‘Shall I not go to Iceland?’ I knew that he desperately wanted to go and so I said: ‘No, I shall be alright’….

I watched him walking down the lane… and I knew that he might never come back but there was nothing I could do but just watch him and remember what he looked like….

No comments:

Post a Comment